Are you sure you want to delete this post?

Source Documents: An Extract from the Chronicle of Ralph, Abbot of Coggershall (1207-1218

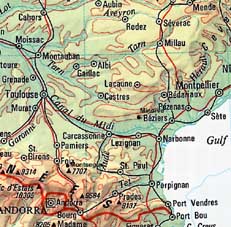

Languedoc

Books

DVDs

Photos

Source Documents: An Extract from the Chronicle of Ralph, Abbot of Coggershall (1207-1218) Ralph was a Cistercian Abbot. This extract from his Chronicle is based on Radulphi de Coggeshall Chronicon anglicanum, ed by Joseph Stevenson (Rolls Series, LXVI [London, 1875]) pp 121-25. A fuller version may be found at Wakefield and Evans, Heresies of the High Middle Ages, §42 (pp251-253) In the time of Louis, king of France, who fathered King Philip, while the error of certain heretics, who are called Publicans in the vernacular, was spreading through several of the provinces of France, a marvelous thing happened in the city of Rheims in connection with an old woman infected with that plague.

This King Louis is Louis VII Cathars were generally referred to in France at this period as Publicans - one of many names for them For one day when Lord William, archbishop of that city and King Philip’s uncle, was taking a canter with his clergy outside the city, one of his clerks, Master Gervais of Tilbury by name, noticed a girl walking alone in a vineyard. Urged by the curiosity of hot-blooded youth, he turned aside to her, as we later heard from his own lips, when he had become a canon. He greeted her and attentively inquired whose daughter she was and what she was doing there alone, and then, after admiring her beauty for a while, he at length in courtly fashion made her a proposal of wanton love. She was much abashed, and with eyes cast down, she answered him with simple gesture and a certain gravity of speech: “Good youth, the Lord does not desire me ever to be your friend or the friend of any man, for if I ever forsook my virginity and my body were once defiled, I should most assuredly fall under eternal damnation without hope of recall.

This William is William of Champaigne, Archbishop of Rheims (1176-1202), son of Count Thierry II of Champaigne and uncle to Philip II of France. He was also a cardinal. At this period almost all senior clerics came from the families of powerful nobles. Master Gervais is also known to history. He was English, but raised in Rome. He studied law at Bolognia. He served not only William, but Prince Henry of England, William II of sicily and Otto IV. For modern readers it may seem odd that a young monk should proposition a young girl in this way. For contemporaries this was not at all unusual. the remarkable point was that the girl declined his attentions. As he heard this, Master Gervais at one realised that she was one of that most impious sect of Publicans, who at that time were everywhere being sought out and destroyed, especially by Philip, Count of Flanders, who was harassing them pitilessly with righteous cruelty. Some of them, indeed, had come to England and were seized at Oxford, where by command of King Henry II they were shamefully branded on their foreheads with a red hot key.

The unfortunate Cathars condemned by Henry II in England were also flogged then sent into the harsh winter weather without clothing. Since no good Catholic would advance the slightest mercy to them, they died of exposure. While the aforesaid clerk was arguing with the girl to demonstrate the error of such an answer, the archbishop approached with his retinue and, learning the cause of the argument, ordered the girl seized and brought with him to the city. When he addressed her in the presence of his clergy and advanced many scriptural passages and reasoned arguments to confute her error, she replied that she had not yet been well enough taught to demonstrate the falsity of such statements, but she admitted that she had a mistress in the city who, by her arguments, would very easily refute everyone’s objections.

So, when the girl had disclosed the woman’s name and abode, she was immediately sought out, found, and hailed before the archbishop by his officials. When she was assailed from all sides by the archbishop himself and the clergy with many questions and with texts of Holy Scriptures which might destroy such error, by perverse interpretation she so altered all the texts advanced that it became obvious to everyone that the Spirit of All Error spoke through her mouth. Indeed, to the texts and narratives of both the Old and New Testaments which they put to her, she answered easily, as much by memory, as though she had mastered a knowledge of all the Scriptures and had been well trained in this kind of response, mixing the false with the true and mocking the true interpretation of our faith with a kind of perverted insight. Therefore, because it was impossible to recall the obstinate minds of both these persons from the error of their ways by threat or persuasion, or by any arguments or scriptural texts, they were placed in prison until the following day.

Translating this into more neutral language, it looks like this lay woman was able to confound her clerical persecutors with some ease - at least as far as the rational arguments went. This is a recurring theme in contemporary records - in the Languedoc, Inquisitors were advised by Bernard Gui not to enter into public debates with Cathars because of the likely consequential embarrassment. On the morrow they were recalled to the archiepiscopal court, before the archbishop and all the clergy, and in the presence of the nobility, were again confronted with many reasons for renouncing their error publicly. But since they yielded not at all to salutary admonition but persisted stubbornly in error once adopted, it was unanimously decreed that they be delivered to the flames.

These events took place before the establishment of the Dominicans and their Papal Inquisition. The process was therefore conducted by bishops and archbishops. Notice that there is no recognisable form of trial - no charges, no defense, no formal process, no attempt to differentiate the roles of judge, jury and prosecution. Note also that the trial is conducted and sentence is passed by clerics. The nobles are invited as passive observers. When the fire had been lighted in the city and the officials were about to drag them to the punishment decreed, that mistress of vile error exclaimed “O foolish and unjust judges, do you think now to burn me in your flames? I fear not your judgment, nor do I tremble at the waiting fire!” With these words, she suddenly pulled a ball of thread from her heaving bosom and threw it out of a large window, but keeping the end of the thread in her hands; then in a loud voice, audible to all, she said “Catch!” at the word, she was lifted from the earth before everyone’s eyes and followed the ball out of the window in rapid flight, sustained we believe, by the ministry of the evil spirits who once caught Simon Magus up in the air. What became of that wicked woman, or wither she was transported, the onlookers could in no wise discover.

An indication of the difficulty in determining which parts of chroniclers' records are reliable. Many contemporary accounts contain miracles and demonic activity such as that recounted here. Another point of note is that stories like this become even more popular in later centuries, and are used to justify a burgeoning industry in identifying and burning witches throughout continental Europe and elsewhere in Christendom. he reference to Simon Magus is to an apocryphal text known as The Acts of the apostels Peter and Paul. But the girl had not yet become so deeply involved in the madness of the sect; and, since she still was present, yet could be recalled from the stubborn course upon which she had embarked neither by inducement or reason nor by the promise of riches, she was burned. She caused a great deal of astonishment to many, for she emitted no sigh, not a tear, no groan, but endured all the agony of the conflagration steadfastly and eagerly, like a martyr of Christ. …

The girl's only crimes were to reject Roman Catholic teachings and to opt to retain her virginity. This was how Cathars conducted themselves in all of the thousand or so such killings of which I am aware.

[Photo]

What did Cathars believe ? Important Events in Catharism Thirteenth Century Warfare - a glossary Basic Cathar Tenets [Photo] Crusaders and their arms Cathar Believers Role of the Church: Cistercians & Dominicans The Cathar Elect Cathar Views of Catholic Belief Cathar Ceremonies What was the Albigensian Crusade ? Catholic Views of Cathar Belief The Cathar Hierarchy Who led the Crusade ? Catholic Propaganda Implications of Cathar Beliefs Who's Who in the Cathar wars Cathar Vindications Where did Catharism come from ? The Papal Inquisition The Cathar Legacy Cathar Terminology Cathar Castles Do Cathars still exist ? Cathar Martyrdom Who were the Counts of Toulouse ? More about Cathars

Languedoc Home About midi-france.info Site Map Links Contact Webmaster Copyright and Legal Search site for:

[Photo] [Photo]

Extract from the Fourth Lateran Council 1215[Photo] window.google_render_ad();

Languedoc Books Guides

Maps

Cathars

Castles

Counts of Toulouse

Rennes-le-Château

Holy Grail

Troubadours

Penthouse in France Penthouse for vacation letting in the heart of Carcassonne in the South of France. Minutes away from numerous historic attractions. Ideal base for Languedoc holidays.